Both bidders for the Games will have to convince the IOC that the Games will address long-term developments goals and sustainability challenges in their cities and regions. The Sustainability Report takes a look

“What we want is for cities to articulate a long-term ambition, and ask how they can leverage the Games to respond to that,” Michelle Lemaitre, the International Olympic Committee’s head of sustainability, told The Sustainability Report earlier this year. “It’s not how the Games can fix that problem, but how they can contribute to that vision.”

A month from now, two candidate cities – Milan and Cortina of Italy and Stockholm and Åre of Sweden – will find out whether they have been successful in their bid to host the 2026 Winter Olympics. It’s the first time that Winter Games candidates have been required, as part of the IOC’s Agenda 2020 (New Norm) strategy, to emphasise how the event will help them achieve long-term development goals and address sustainability challenges.

While a report from the IOC’s Evaluation Commission (published last week) stated that both candidates had “fully embraced the Olympic Agenda 2020 philosophy”, the document highlighted that there was work still to be done in terms of articulating that vision and putting the necessary things in place to achieve it.

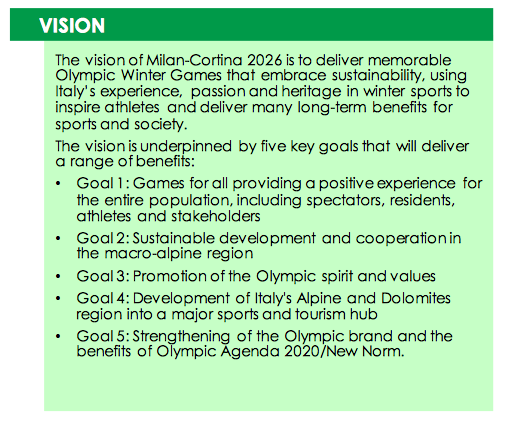

Milan and Cortina has opted for children, and the development of their habits, as a key component of its sustainable development plan for the “macro-alpine” area that includes Milan, Cortina and the surrounding regions. It has ambitiously stated that the Games will contribute to its vision that all children born post-2010 will play sports regularly, recycle three-quarters of the waste they produce and use sustainable means of transportation only.

The Evaluation Commission commented that while it was “laudable” to set goals for all children, the plan could be “overly ambitious” as it falls outside the direct control of the Games delivery bodies.

Statistics produced by the World Health Organization in 2018 about physical activity levels in Italy revealed that while 82% of 8-9-year-olds were undertaking a sufficient amount of physical activity, only 11% of 11-15-year-olds could claim the same. This suggests a significant shift would be required – as would close collaboration with Italy’s health and education ministries, as well as a host of other private and public sector organisations.

Italy, however, has one of the best recycling rates in Europe, with NGO Kyoto Club actually crowning the nation the best with a rate of 76.9%. Methods to instigate incremental improvement may be necessary rather than a large piece of work around behaviour change in this instance.

Large-scale developments

In Milan/Cortina’s favour is the fact that the Evaluation Commission has noted that its bid dovetails nicely with two large-scale development plans proposed for the region: the Milano 2030 Urban Development Plan and the 2018-2023 Regional Development Programme for Lombardia.

The former is a development plan comprising a large-scale sustainable mobility project, and initiatives around jobs, social housing, social inclusion and urban regeneration. The latter programme is focused more on sustainable development in mountain areas and promoting sustainable tourism.

Part of Milan’s 2030 Urban Development Plan is to develop a “green, liveable, resilient city” by developing seven abandoned railway yards into “environmental regeneration areas” complete with housing and other community services.

A Green Procurement Programme for the region has also been proposed – mirroring a sustainable sourcing programme that will be implemented for the Games that will comply with criteria set by the Italian Ministry of Environment. Milan/Cortina has also pledged to use 100% renewable energy for the multisports event.

Social inclusion

For Stockholm/Åre, one of the main sustainable development projects focuses on integration – more precisely, the social inclusion of migrants and refugees who have made their way to Sweden. In 2015, 162,877 people applied for asylum in Sweden, and over the last year, more people have arrived in the country than those who have left.

Indeed, Sweden has accepted more migrants per capita than any other European Union nation over the past five years, with 400,000 compared to the overall population of ten million. And the influx of arrivals has generated support for the far-right, with many migrants facing racism, discrimination and marginalisation.

Sport has often been put forward, by the European Commission in particular, as an effective way to facilitate social inclusion and the integration of migrants, particularly displaced people. However, the Evaluation Commission has called for “additional work and further engagement” on how the Games would support this programme and other long-term visions.

With all of the funding for the proposed Games coming from private sources at this stage, it may be a challenge to marry the Games blueprint with visions laid out by the regional and national government.

Similarly to the Milan/Cortina plan, Stockholm/Åre is hoping to stimulate dwindling sports participation among its young people through a successful Games bid. Only 13.9% of Swedish adolescents (aged 11-17) reach recommended physical activity levels.

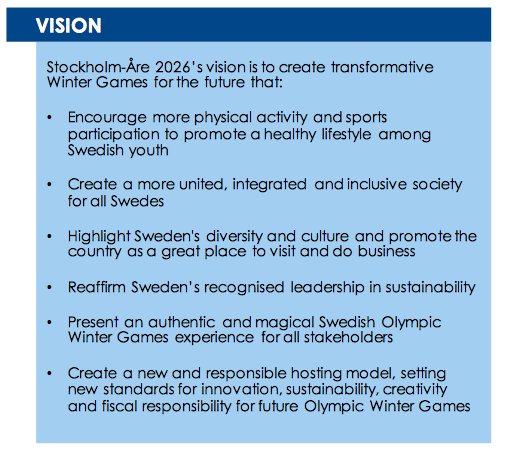

And Sweden is confident that the Games will help cement its place as a “world leader” in green living and sustainability, as well as a major technology and environmental engineering hub. According to the Environmental Performance Index, the Scandinavian nation is the fifth most sustainable country in the world. However, a study by RobecoSAM published in December last year put Sweden at the top of the list.

In terms of green living, Swedes are among the most conscientious in Europe. European Commission data found that 40% of inhabitants have purchased eco-label food and that 88% of all aluminum cans and PET bottles are in the recycling system.

Sweden also has the highest percentage of renewable energy in the EU (52%) and plans to become fossil fuel free by 2050. This year’s FIS Alpine World Ski Championships in Åre were 80% fossil fuel free, and according to its bid book, the Stockholm/Åre 2026 Winter Games would follow a “fossil fuel free, climate-positive model.”

Venue concerns

But the IOC Evaluation Commission has queried some of the bid’s venue plans from an ecological point of view. The new cross country and biathlon venue proposed for Botkyrka will be built on the site of an old quarry, raising concerns about potential soil contamination and the “impact of water quality of a nearby lake.”

The Commission also warned that three of the existing venues being earmarked for the Games were “located in or adjacent” to protected nature areas and that organisers needed to take “particular care in planning.”

Sweden’s high sustainability scores are partly derived from the fact that it is quick to respond to environmental threats, and IOC Olympic Games executive director Christophe Dubi said that Sweden’s “track record” with the environment has given the Commission “a lot of guarantees.”

“We are saying for the protected area that we have to be very considerate when it comes to the overlay development, and especially elements such as temporary lighting that can have an impact on the environment,” he said.

“For the quarry, our experts were very clear that we have to look at the environmental conditions of the quarry to see whether there is some remediation work to be done, and also to make sure that in the future this environment will be fully protected.”

The weight that sustainability and legacy is (and should be) given during the bidding process for an Olympic Games has long been debated, but both candidate bid books and the Evaluation Commission report suggests that in this contest it is crucially important.

Whoever wins the bid will have to grapple with large and complex issues beyond organising a sporting event. However, if the 2026 Winter Olympic Games genuinely accelerates sustainable development as proposed it will be a huge feather in the cap of the IOC and its New Norm agenda.

Which bid has the most ambitious or achievable development goals – and can the Games really aid them? Let us know in the comments below.

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *