Elite athletes set a goal before they know how they’ll achieve it – the same mentality can be adopted by sports organisations to address climate change, say Joie Leigh and Claire Poole

The parallels between the journey of a professional sportsperson, striving to become a champion, and the journey of a sports entity trying to play its role in combating climate change is more similar than you might think. Setting goals that can seem overwhelming, working through setbacks, overcoming mental barriers and, in some cases, facing external criticism or doubt is part of the territory for both endeavors.

If you’re working in the sports industry and trying to make your organisation, club or sports more sustainable amid constant challenges, your ambition could be aided by adopting the athlete mindset. Here’s how to achieve that in six steps:

1. Set the goal

Athletes set themselves goals pretty early on. It could be competing at the Olympic Games, becoming World Champion or winning an iconic race or tournament. It’s usually a BHAG (big hairy audacious goal) in the future. At this stage it’s unlikely the athlete even knows if the goal is achievable, but we can take the lead from the belief of setting the BHAG in the first place and then mapping out what it takes to make it happen.

Often in sport operations when we’re looking at being more environmentally-friendly, we think incrementally. A reduction here, a campaign there. This is amazing, and there is nothing wrong with starting small – but with time running out, let’s try and take a lead from athletes in setting a bigger goal.

2. Have what it takes

An athlete’s mindset is based on commitment. You have a dream, an aspiration of what you would like to achieve in the future to win big competitions or be the best in the world, but to begin you have to fully commit. There is an understanding that success is not guaranteed, and the journey is often embarked upon without really knowing how to get there. There will be uncertainties, setbacks, challenges and difficulties. However, deciding to go after it anyway and continually adapting, reorienting and improving towards achieving the goal is a constant mindset.

When we watch athletes and teams perform and feel inspired, we think we are inspired by the achievement itself – the medal, the trophy, a personal best. Often, we are actually inspired by the mindset that person or team has, which has led to that achievement. The only chance of success comes through being totally committed to the goal. It’s the mindset of commitment and intent that we admire, and that’s something we can all do.

A strong culture with clear vision and values makes the ‘bigger goal’ more tangible and is a group contract you have signed up to. This enhances the level of responsibility to not let yourself or your teammates/community down. The ‘bigger goal’ underpinned by the values and behaviours you hold strong individually and collectively not only becomes the ‘how we do things around here’ expectation behaviour wise, it also becomes something everyone can connect to in both the short and long term. So, whether you’re selected for the next tournament or not, having the bigger goal keeps you moving forward through the good times and the bad.

For sports organisations on the sustainability and climate mitigation journey, set a goal in the first place and commit to achieving the goal, then ensure your company culture supports this. Maybe your goal is to go zero waste, being entirely net zero on emissions at a certain point in the future, gaining a certification like ISO20121 or winning an award for your sustainability efforts. Whatever it is; set it now, commit to achieving it and work to ensure your company culture supports the goal.

3. Work out how to get there

You’ve got the goal; your organisation is committed. What now? In sport, as in any area of life, the process of reaching a long-term goal ultimately relies on meeting continual short-term goals. Whether that’s the incremental gains in the gym that allow you to be more robust, or the honing of a particular skill so you can perform it under increasing pressure – setting these intermediate goals are key to empowering you in the journey towards the long-term ambition.

Doing small things every day, from planning and preparing the things you eat to make sure you’re fuelling to optimise body composition and energy levels, to going through mobility exercises before even setting foot on the pitch to warm up. It is the expectation and trust that doing small things every day adds up and really matters. You have to believe in doing small things every day because consistency is crucial to creating a big impact over time. It is about always having faith in the discipline and controlling what you do today to achieve a bigger outcome in the future.

When they’re on their journey towards the BHAG, athletes recognise that difficult decisions sometimes have to be made for the greater good. The brutal reality of elite sport is that there will be winners and losers, and it really hurts if it doesn’t go your way, but in a team sport it always comes down to the greater good of the team. A strong sense of team and purpose ensures that the difficult decisions are rationalised and palatable.

Maybe you work for a sports organisation that is starting to look at sustainability as a concept or maybe you’re already on the journey. Either way, you may not yet have a clear path to reaching your goal, but take solace that elite athletes at the top of their game don’t know either. Set continual short-term goals; if your goal is for your event to be zero waste, think about the low hanging fruit to reduce some elements of waste as soon as possible, then start to try and influence more systemic change with new suppliers and waste partners in the following years. Secondly, do small things every day. No matter what your goal, consistency is better than rare moments of greatness.

4. Strategies to improve

We’re human, we’re fallible and we will mostly take the path of least resistance as we go about our lives, so how can we try and prevent falling into the trap of being lazy? In sport there is a tool called constraints-based training. This tool is used to force adaptations of better decisions when unhelpful habits are likely to creep in; usually during periods of fatigue or in high pressure situations. It could be playing in different areas of a pitch or overcoming a particularly lazy technical habit. Often, it’s initially annoying or challenging for the athlete, however the constraint is a crucial element of influencing an improved performance.

We have begun to see parallels of constraints-based training in the world at large. Charging a nominal amount for plastic bags is a great example of this. Despite initial chagrin, some statistics in the UK show that the seven main retailers issued 83% fewer bags in 2016/17 than in 2014. We’re starting to see these changes at sports events too with, for example, initiatives like deposit schemes for reusable cups to replace disposable and plastic cups. This is a massive area worthy of further exploration as we continue on our journey – to both increase the sustainability of sporting events and to support positive behaviours more generally.

5. Overcome the mental barriers

For athletes, some of the biggest mental barriers are doubt, a fear of failure and temptation to take the easier route – all three of which can be debilitating. To succeed you have to be aware of these things operating in your psyche and take the initiative to overcome them. One of the most powerful things Joie learned to try and counteract these barriers was a perspective of the true meaning of courage. Courage can be defined as the ability to show up in the face of vulnerability and to stand up even when it’s difficult. When the odds might be against you, when you feel the pressure or when you might feel small. The value in being courageous is not focused on the uncertainty of outcome but on the certainty of doing what you know if right.

Theodore Roosevelt, the 26th president of the United States, epitomised this mindset perfectly during his oft-quoted ‘Man in the Arena’ speech:

“It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.”

Within sport and sustainability – and the wider challenge of climate change particularly – there are many mental barriers to overcome. The person driving change within the organisation is often alone, it can be an uphill struggle to get initial or continued buy-in from leadership. Great ideas often fall short of being actioned because of reasons beyond their control. It’s a struggle and a journey that often happens in the face of wider naysaying or a focus on other priorities. When it comes to overcoming these barriers, remember that you are part of a team; a global team working towards sustainability within sport. There are hundreds or thousands of passionate people just like you, working towards the same goal, within their organisation or sport, so keep focusing on the process.

6. Achieving the goal

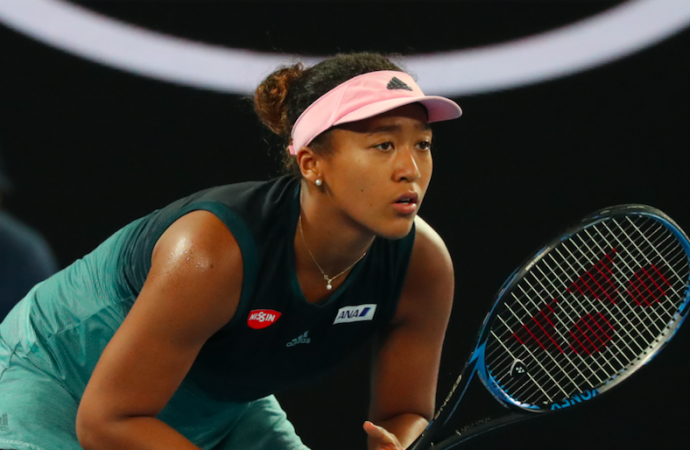

Last but not least; achieving your goal – the holy grail. Spoiler alert: in sport, sometimes gold isn’t the outcome, and even when it is – it’s not the sole measure of achievement. It sounds counter-intuitive; gold is what you were striving for, and training for, and sacrificing for. However, the culture and legacy of the effort is a huge part of the achievement. Understanding this enables success to be derived from the whole effort; as tennis icon Arthur Ashe put it: “Success is a journey, not a destination. The doing is often more important than the outcome.”

Our spoiler alert within the sports movement to combat climate change is that there are no medals. We may not even be around to see the fruits of our labour. ‘The doing is often more important than the outcome’ is what must define our efforts. It’s also all the more reason to put continual and tangible short-term goals for our organisations in place, bringing value to staff, consumers and fans by achieving them and taking the time to celebrate them. Our work is a long game, but it’s up to us to keep the dream alive.

Claire Poole is the founder of Sport Positive Summit, taking place in March 2020, and was a consultant to UNFCCC on the inception of the Sports for Climate Action Framework. Joie Leigh is an advocate for championing sport and sustainability and a former Great Britain and international hockey player.

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *